Instructional Methods

Creating an Awesome Class

Lecturing

A great lecture inspires students, especially if you’re sharing your passion for the

subject. It is not, however, when or where learning happens. Why? Long lectures are

challenging for students to acquire and retain a lot of information all at once and

leave little room for you to measure their comprehension by the end of the class.

Solution: break up your content into “microlectures”--brief (under 10 minutes) lectures

that are digestible and ideally lead to an activity. Videos should also be “micro”!

Not just for your students’ benefit, but also for you, over time, as you swap out

some content, it will be easier to re-do a 5 to 7 minute video versus a 75 minute

one.

For additional information, view the following resources.

Pro Tip!

Ask students (especially early in the semester) how the pace is and adjust as necessary. This can be low-tech with a simple thumbs up/down. Why? It communicates to your students that you care about their learning!Leading a Discussion

In a lecture, you convey content. In a class discussion, you allow students to grapple with that content by problematizing it. Unless you have extremely small classes, it is best to have students work independently or in groups first, giving them time to think through your prompt.

Setting up Productive Group Discussions

- Determine what students should get out of the discussion (work certain problems, critique an artwork, assess/diagnose/act, etc.).

- Choose the activity that will best help students reach that objective.

- Determine the grop size (2-6 is common with just 2-3 students if a simple task and/or you are trying to get students to speak; larger groups are ideal for generating a lot of ideas).

- Determine how long they will work in groups

- Be Clear on the task the groups are assigned and what the deliverables are.

- Prepare in advance how you will debried at the end of the discussion

- Are there specific takeaways students should have?

- Was there incorrect information that was said that you can correct?

- Any neglected points you want to hit?

Sustaining Student interest While Classmates Share

- Select random groups to report out (try to remember to choose different groups each time!). When responses get repetitive, it is time to move on.

- Not every group must work on the same thing! Students are motivated to listen to others

when the content is different. Try

- Assigning each group one pieve of the whole [see "Jigsaws" in Teaching Strategies]

- Asking them to apply a concept in a creative way [see “Forced Analogies” in Teaching Strategies]

Structuring Class Time

Lectures are often the primary instructional strategy for large classes, but we know from research that your students won’t learn or retain much by sitting in class just listening to you lecture, memorizing content, and regurgitating answers.

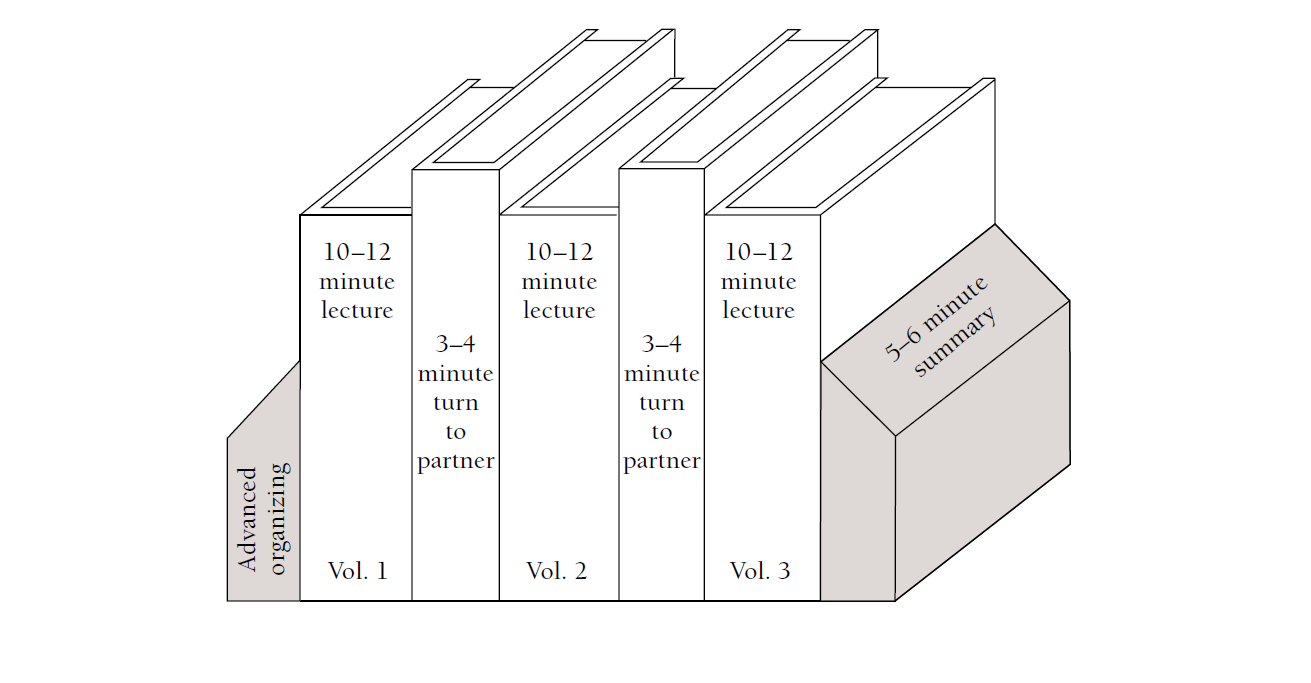

Chunking Lectures

But what about those long, beautiful lectures that you’ve given for years? Chunk them!

Divide content into microlectures and insert in-class activities in between. Which

chunks should I keep?

⦁ Key points and general themes

⦁ Especially difficult material

⦁ Material not covered elsewhere

⦁ Examples and illustrations

⦁ Material of high interest/relevance to students

Bookending Lectures

One way to structure the class is it “bookend” it.

⦁ Open with an engagement activity.

⦁ Alternate between lecture and student work.

⦁ Close with a summary activity or guided reflection

Flip it!

What is a flipped classroom?

In a traditional class, new content is introduced by lecturing (providing background, stating definitions, and sharing simple examples). Instructors hopefully make time for some in-class activities or discussion that check for understanding, but higher-level tasks (applications, analysis, evaluation) happen outside of class, such as homework, projects, or exams that happens days or weeks later.

In a flipped class, students’ first contact with new ideas happens before a class session, in the form of structured activity. This could be a recorded video [see microlecturing above] or a reading that students can access in Canvas, which is accompanied by exercises that help students process that information. When students come to class, they are now already familiar with some of the vocabulary, key issues, or players, and are ready to practice higher-level tasks.

Does it increase the grading load?

No. To explain the flipped classroom in terms of Bloom’s Taxonomy [see full explanation here], a traditional class only has time for the lower third of Bloom’s with the upper two-thirds relegated to students working on their own and/or to a summative assessment that happens later in the semester. The steepest part of students’ learning climb is happening away from the professor.

On the other hand, consider the flipped approach as also flipping when and where cognitive tasks take place: the bottom third of Bloom's Taxonomy (Remember/Understand) is now done before class, and the middle (Apply/Analyze) is now done in class...

The remember/understand tasks completed before class would be checked in Canvas with a quick quiz or exit ticket—neither of which require your grading time. The in-class apply/analyze tasks also do not necessarily require grading. Structure the class time with case studies or problems that small groups can work on and then share with the rest of the class. As you (and their classmates) give feedback (which at this stage is far more valuable than a letter grade), you can simultaneously mark student work with a check or an X or any simple notation system.

Pro Tip!

Reinforce the lower and middle thirds of Bloom’s with a graded checkpoint later, such as a weekly quiz.

Managing Large Classes

When it comes to large, face-to-face classes, it is tempting to be a “sage on the

stage” and lecture the whole time, but it is 100% manageable to create student-centered

learning experiences!

To keep students continuously engaged, chunk lecture content into smaller segments

(15 to 20 minutes) and then switch gears by involving students in active learning.